Carne de Dios is a striking tale which tackles a brutal and challenging period of South America’s history. The production, led by writers and animators Patricio Plaza and Gervasio Canda, seeks to reconcile the ancient fissures experienced by the continent, by bringing together an all-star Latin America team of over a hundred contributors from countries including Mexico, Columbia and their home country of Argentina. They form two-thirds of the Argentinian animation collective Ojo Raro, a studio and platform that champions animation from the Latin world and beyond.

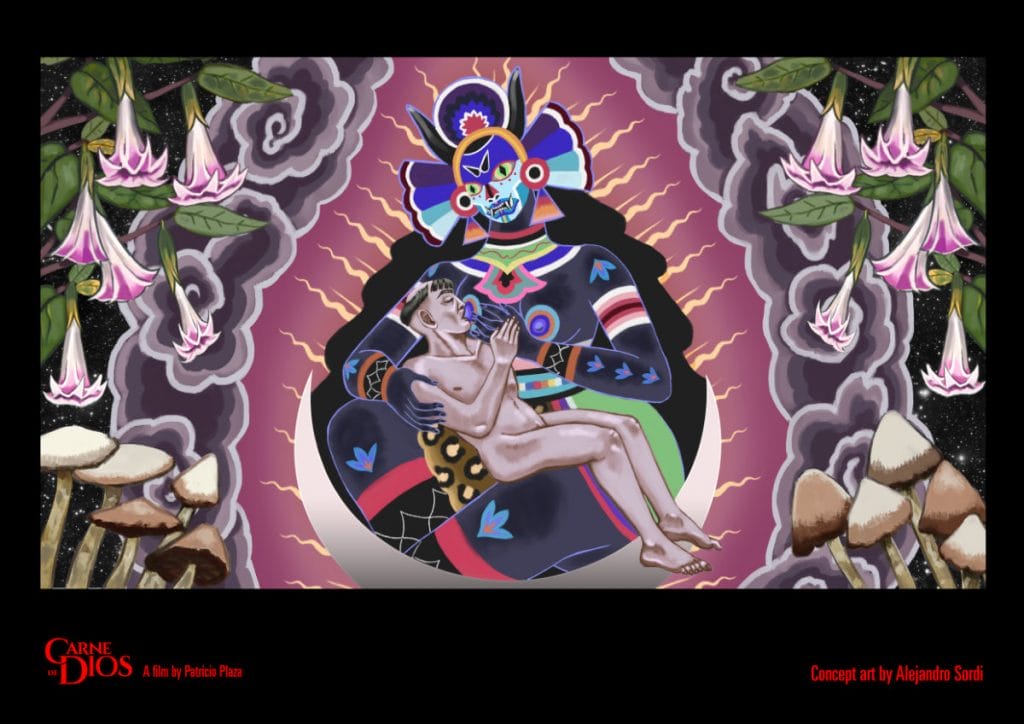

The film, which runs for about 21 minutes, includes horror elements mixed with political, religious and historical themes. The resulting combination is a phantasmagorical nightmare that evokes the dread and disturbia of the dark unknown, and hints at retribution for colonial evils. Created with a unique style that evokes feelings of violence and psychedelia, Patricio and Gervasio seek to challenge the typical notions of beauty and aesthetics made popular in Western animation. In their words, the Global South has something to add to the conversation, and a story that’s well worth telling.

The duo, responsible for directing and leading animation on the project, gave their time to speak to Toon Boom Animation about how they created their violent and visually bold film. They share some of the journey from production to winning a string of awards and nominations at festivals around the world. Patricio and Gervasio also share insights into how tools in Harmony helped them create a unique rough-lined finish, and during the cleanup stage on the shadows, lights and effects that give Carne de Dios its uniquely haunting atmosphere.

Please introduce Carne de Dios with a short summary for our readers…

Patricio: Carne de Dios is a 2D animation short film. It’s 20 minutes, which is quite long for a short film. It’s based on the writings of Spanish friars during the colonization process in Mexico. Those texts inspired me to write a horror fiction film. It’s a fantasy folk-horror that speaks about the persecution of other forms of life, ways of living and spiritualities during the evangelisation process in Latin America during colonization times.

It’s our appropriation of those texts. We used them to build a tale that imagines what would happen in the mind of one of these Friars if he had to endure in his own body one of the native rituals that he has been persecuting and hunting down. It tries to imagine through animation what this experience could have been.

Please introduce some of the key team members at Ojo Raro and their roles on the production…

Gervasio: I’m Gervasio Canda and I’m one of the partners at Ojo Raro. Patricio told me about this story about a thesis he did in Mexico and that he wanted to create a short movie about it. I got super hyped about the story and the fact that it was something else; another story to tell — a fiction about what could happen. I got interested in the project. I’m living in Canada and we didn’t actually know each other before, but I told Patricio I wanted to participate somehow in this project because I love it. That same year we started working together and doing a little bit of concept art.

I work in video games, working for Epic Games, so I felt this project connected me with a different type of storytelling. With content that is more edgy, more controversial and an approach to style with more grotesque characters that gets away from the more hegemonic designs that we know of the major studios. The idea was to do something different from the beginning.

After that, we’ve become good friends, and we now run Ojo Raro with Paulo Boffo. For a little over two years, we were working together and doing shorts together — as well mentorship and participation in festivals. We believe Ojo Raro is a platform, more than just a studio that produces our own content. Our idea is to push animation and help other people who have really good stories to tell to see the light, and help with our knowledge and our contacts.

The core members on Carne de Dios include myself, Gervasia Canda (art director), Diego Polieri (character designer) and El Sike (backgrounds). There were around 100 people who worked on the project, but this was the core team. It was a huge project, but not with a lot of budget. The project is a co-production between Argentina, Mexico and Columbia, so it’s a collaborative effort between these three countries. It’s a shared vision because the same story happened pretty much all over the continent of Latin America. A lot of people relate to the project in that sense and we built a beautiful team. I’m really proud that the film was made in a Latin American co-production.

How would you describe the unique style of animation in Carne de Dios?

Patricio: We don’t have a particular name, but I’d say it’s a little rough in that it’s not completely fluid. As Gervasio was saying, we wanted to move away from the traditional 2D cel animation approach which tends to be more commercial. Mainstream animation tends to be more fluid and the lines are super clean.

We wanted to move a little away from that and work more with comic book references and also Latin American visual artists, from popular art forms like Mexican muralism and artists like Oswaldo Guayasamín from Ecuador. Of course some of our influences are also from Western animation and European animation too, but we wanted to keep that rough look; both in the visual style and the animation. We animated alot on threes and fours to make the movement a little bit more rough. A bit more violent, I would say. We wanted to be a bit more grotesque, in many ways. We thought that if we worked with a very fluid animation it would move away from what we wanted to create. I think the visual style and the animation are quite related.

We wanted to move away from the usual approach in Western animation of the idea of visual “appeal” and making the characters follow ideas of beauty, and notions of what is beauty and what is not. For example, making things more rounded, making things more appealing — we wanted to try and move away from that, make things more rough, and work with the idea of ugliness. Moving away from hegemonic beauty, and proportions and the Western approach to animation which is very standardised. We wanted to work against those ideas.

Gervasio: I think the fact that we had four characters, and three of those characters are native, we really wanted to differentiate the Friar character. We tried so many noses before finding a size of nose that would be iconic and recognizable. That was really interesting, trying to push the boundaries of how much expression we can push to get something unique, and as yet unseen.

I think this relates to the feelings and sensations we wanted to create with the short. This feeling of uncomfortableness. All that goes together with the technique and the backgrounds. We worked with watercolour, which was a little hard, but we wanted to create textures and do things analog — painting watercolour to create textures in the background and then on Photoshop we applied the colour by taking the grain with all the textures. This approach is totally different from something that goes on TV or a series or movie from the majors. That was the direction we wanted to push it.

How did you approach conveying horror in your animation approach?

Patricio: It’s a horror film, so it has to be a little bit disturbing in some sense! That’s why we wanted to move away from the above, using a lot of black shadows and working with the line to make it super rough. That’s the approach, because most of all this is an adult’s horror story. It has to be disturbing, so we tried to work that both visually and in the animation.

Gervasio: We put a lot of effort also into the colour script to really differentiate the scenes. There’s the whole trip of the Friar, passing through different rooms and different situations, conveying different types of feelings.

There was the moment he encounters the monster and how we coloured that. We did a lot of tests to come up with a colour that felt like you were inside and comfortably numb. The colour we worked with a lot to create something that grabs your attention and makes you feel like you’re advancing the story, at the same time differentiating when he is under the effect compared to real-life, so to say.

Can you share some of the visual or stylistic inspirations behind the project?

Patricio: I would say there are many influences. We had influences from Argentina, which has a tradition of illustrators, comic books and graphic novelists. One of them is Alberto Breccia, he was a total master of the comic book art, and an auteur in that sense. He had a very particular style, working usually a lot with black, and with brushes. I mentioned Latin American art, but I think what is interesting is that, as Latin Americans, we have a huge lineage of visual artists and cultural diversity.

But at the same time of course, I was born and raised in the 80s and 90s, so we have influences from Japan and Western animation too. There’s a mixture, a sort of appropriation of all of those influences that we’re trying to do. So we have influences from Evangelion but also from French animation, like Sylvain Chomet — and of course Disney animation. It’s this mixture of influences; trying to appropriate that to tell something new.

We received all that during the formation of our imaginations, especially during childhood. We say that now that we’ve grown up, we develop our own ideas and mix this all together to give something back. This is our Latin American answer to everything we’ve received for so many years. In that way, it’s a political answer too. It’s saying that this is another voice here, coming from the South. We have something to tell here also, especially in animation which is a medium that’s been so conservative over time.

So we are trying to push the boundaries, as Gervasio said, of the medium itself. We are trying to change the animation scene a little bit. In Latin America there have been a lot of films in the past ten years that are taking genres like horror and fantasy to make a political statement and to speak about the history of our continent. I think that’s super interesting, because there’s a movement — I call it political horror in Latin American animation — which is particular to what’s happening in Latin America right now.

You should pay attention to that! Bestia from Chile, for example, and of course lots of animation coming from Mexico and Guadalejara that has a long tradition. There’s a lot of people working with these topics and this cinematographic genre.

How were the supernatural, ritualistic elements of the film created?

Patricio: There are several parts to this. As Gervasio mentioned, we worked a lot on the colour script to create the mood of each scene, to give them a particular feeling. In terms of the rituals themselves. They are based on the Mazatec rituals. The Mazatecs are a culture from Oaxaca in Mexico, from the Sierra in the Mexican mountains. They have kept their original, pre-colonial rituals.

They use plant medicines and with mushrooms, for traditional medicinal use. That’s why the Friar character has to go through this ritual, to recover his health. The ritual itself is based on the traditional use of mushrooms by the Mazatec culture. I was in Mexico for several years, going back and forth between it and Argentina, studying and researching. I found out about the writings of these friars from the 16th Century. They referred to this type of ritual as demonic, of course. They thought that the natives used these rituals to connect with their own gods, which were demons — from the Westernized viewpoint. That’s why the friar has to go through this experience, to find out that maybe the demons are inside of you, and not out there.

In the frame of the original Mazatec ritual, with the Mazatec language of course, the Curandera — we would say the shaman — speaks in Mazatec, their own language. The Friar is distant from that culture, and in that sense, the viewpoint of the entire film moves away from the native viewpoint. Because I am not native, I am not Mazatec, and I have a Western point of view. It’s more about watching the entire ritual, but from afar. Not knowing what’s going on in that ritual apart from that you are sick. Having to accept that he has to eat these mushrooms to recover from this sickness. It’s keeping the mystery of those rituals from the viewpoint of a Westernised person who doesn’t completely understand what is going on.

At the same time, we have the influence of syncretism, which is the process of when a colonial culture imposes its viewpoint, in this case in terms of religion. Imposing Christianity over a huge diversity of cultures that had other views, with many different types of gods or even animistic forms of spirituality. Syncretism is when the culture that has been oppressed finds a way of resisting and keeping its own culture alive under the new, official religion that has been imposed.

Syncretism is also an expression that is widely spread in visual arts and culture itself. The representation of Jesus for example, that appears in the film, is not the Jesus you would find in a European church. Those representations are mixed between the old traditions, the native cultures that were there, and this new culture that comes and somehow imposes its worldview and its own gods.

Syncretism, I think, is a very particular element in culture, visual art and in religious art in Latin America. It’s part of this ritual experience too, the mixture of spiritualities and different sorts of rituals that merge. It’s interesting because I think that syncretism is somehow a form of resistance, but at the same time, it accepts that this is a new thing we have to deal with, a religion that’s been imposed — but finding a way to keep your old traditions and not just let them go away. That was the ritual approach.

What techniques did you use to create the psychedelic parts of the film?

Patricio: For the psychedelic experience, there were many stages. Sometimes it’s more psychological, but at the same time it’s super physical. The beginning of the trip is more related to his body, his fear, and finding his inner demons. But as the trip intensifies, he gets separated from the ordinary reality and he goes into this other world. We would call it the inframundo, or the underworld. This is kind of his own subconscious mind and how he’s feeling the experience. It’s like he’s reaching the peak of the psychedelic experience. For that moment, we worked with Esteban Azuela and Salvador Herrera, who are two Mexican animators who did this fractal void, the most abstract part of the trip, and at the same time the peak. It was going from the ordinary perception to the most abstract and exaggerated psychedelic moments. I worked with Gervasio a lot on the colour and ambience of the scenes, because each scene has its own pace and its own emotional approach. The way we approached it was; the first time it was going to be super dark with lots of elements from the underworld, this river with the souls of the victims. Then we have a moment that is calm, where he gets into the cave, and the pace changes like a wave. It’s a wave that intensifies, it goes down and goes up, it’s like a joyride — or a nightmare-ride, I would say. A rollercoaster.

Gervasio: To add, we were super meticulous with designing the sets. We knew a lot of things would happen in the house. We designed the house keeping in mind all the elements that the shaman would have, like where she would sit, and the cornfield that we used to have the Jesus Christ figure at the beginning of The Friar entering this trip. So we used something grounded and something known and changed the size and had it chasing him in this cornfield. Which was used on purpose to create something more grounded in reality, to create a passage between something connected to reality and something going more crazy. When he’s in the cavern, and he’s more inside the trip, we used Coatlicue, the goddess of fertility. So we used the imaginary there. He’s with this monster in this intimate moment before the trip’s peak.

To create those fractals, we used imagery from the books that Patricio found in the library in Mexico. They were real drawings done by the friars from those times. At the moment you might not see it, because the idea is that you are in this tunnel and it comes in waves, but you can see some snakes, and Coatlicue in there.

Patricio: It’s good that Gervasio mentioned this because at this peak of the psychedelic experience, in the fractal tunnel, most of the imagery there has been taken from the Glasgow University manuscripts, which are texts from the friars in the city of Tlaxcala, from the 16th Century, where they burned down a lot of temples, an act which they drew records of. These friars were the ones who were writing this history, and at the same time drawing this history. If you look up the Glasgow manuscripts, it’s crazy, because they’re drawing themselves burning the temples and there are demons coming out of them. They are, in a way, confessing that they burned down the temples, and according to the images, lots of native were hanged – it’s seriously violent. We used those images from the historical document to make this trip sequence. It moves really fast, but if you look at it closely you’ll see all these representations of these monks, the demons and all the visuals taken from the Glasgow manuscript. It’s the original confession from the monks themselves.

What is the giant’s breast and nipple meant to represent?

Patricio: Usually I am not fond of giving a unique explanation to each element of the film. I think it should be open to interpretation and I like to keep it ambiguous. This is so the audience can interpret it in their own way and find their own reading of the films. When the wooden Christ comes to life, it’s the first supernatural element that the Friar experiences. It starts being a demonic representation of Christ — it’s made of wood and it’s super dry. The process of the character is related to going to this inner cave of his conscious mind, which is this very wet place; I like working with the contrast between what’s dry and what’s wet and the humidity.

I don’t want to get psychoanalytical, I’m not a fan of Freudian interpretations, but of course there’s something related to a sort of regression that the character lives in his psyche. His desire is, of course, unleashed. Due to the psychedelic experience, where you get in touch with your deeper subconsciousness and with your own desires. At that moment there is this entity, which as Gervasio said, is loosely based on Coatlicue which is one of the goddesses of the Aztec pantheon. The Mexica culture has many, many deities, and some of the feminine deities in the Aztec culture are related to fertility, and to nature themselves and the growing of the crops. These are the ones that, when Christianity arrived, were taken and turned into the Virgin Mary. They were a good aspect of nature, that gives back, but there’s another aspect to this nature which is about death, destruction and descomposición, or decay. It’s another aspect of nature within the full cycle, for creating life, then death, then life again.

This particular deity, Coatlicue, is also the mother of the gods, and in representations she has lots of breasts and lots of skulls. She’s the mother of the gods but also the devourer of men and gods alike. So it’s a relationship of being totally persecuted in a nightmare with all these creatures where he finds himself in a totally regressive state. Where he gives in to this deity whether it be a goddess or a demon, whatever you want to see in it. He gives in to that and accepts that. It’s a stage of release for the character. He’s bringing to this strange place his own culture and religion, and christianity especially has always been very repressive towards sexuality. This is the place where the character unleashes his inner desires, through this primitive relationship with this deity creature.

It was interesting for me to work on this more regressive state of the character. It’s also the only moment the character is enjoying after being super persecuted and living his nightmare – he’s enjoying this moment. He sees in the creature the incarnation of the mother archetype, a dark mother archetype, I would say. The Virgin Mary is only one aspect of the female archetype, in many cultures. You can also relate this to goddess Kali in India – they all have these different aspects. Usually what would be interpreted as darker aspects of nature such as death, destruction and decay has been banned from Christianity’s aspects of the female deity, and has only kept the one which is good, is the mother and gives. It’s important to recognise that this is a key element to the colonial approach of religion. They decided they were going to put a church over every temple, and choose which aspects of the gods they were going to keep for their own interests.

This is something that Gloria Anzaldua, a queer Mexican author who lived between the frontier of Mexico and the United States and wrote this book called Borderlands. The quote at the beginning of the film is from her. She speaks deeply to this issue of cutting down an integral part of the feminine deities and moving them away to the realm of the demonic. That’s pretty much the same as what they did with the use of mushrooms. They found the demonic side of it and accused them of talking to their own demons.

Can you speak a little about the context behind Carne de Dios and its decolonial message?

Patricio: It’s there, and that’s why we like to work in this cinematic genre so much. The film is, most of all, a horror film, and it can be enjoyed in that way. You can watch the film and be entertained by what’s happening and the characters, the action, the different moods and emotional stages. But at the same time, it’s political horror. It’s based on the history of our continent, and it’s something that still goes on. The implications of what happened are still happening today in a lot of senses.

It’s decolonial in that sense, but at the same time, it’s important to me to emphasize that there were many different forms of resistance. It wasn’t something that just happened. There is no going back in many senses, but we still have many forms of resistance today. In that I find hope, in all of this. It’s a discussion that is still going on, will be going on and is not solved. It needs to spread as it’s something that happened that cannot be erased. We need to have some intellectual honesty to say let’s talk about this. I think fiction and horror and fantasy can be as political as a documentary, in that sense. You can have a film that’s very far away from reality but at the same time it’s speaking about what has happened, it’s speaking about history — even if it has a huge monster in it. That’s interesting to me and I think fantasy and imagination is political in that sense.

There are many forms of resistance. That’s the core of the film; speaking about this. What’s interesting about filmmaking for us is the experience itself of having a body experience when watching, that affects you emotionally and in your body. But at the same time, to open discussions, like when you finish a film and want to speak about it with someone else on what it was about. That’s our main aim; to help open up discussions.

I don’t think art should solve political issues, but I think it helps to open up discussions that have been silent for a long time. Especially with animation that has been a tool for creating other forms of imagination that have been normalized under hegemony. That’s why it’s important for us to make animation in South America and speak about these topics even if it’s difficult. It’s not easy to make these kinds of films, but at the same time it’s very important to spread these discussions. It’s not only Latin America or Europe, but this has happened in many places in different forms. Conflicts have been similar where, from a supremacist viewpoint, one culture believes it superior to the other. That has led us to so many problems in this world, and the belief that there is only one way of being in this world. That is what is taking us to ecological collapse.

Gervasio: Being creative in which time and era we tell the story is important. If you look at the characters and the natives, they have already been influenced by the church, like in their house where there’s a Jesus, and the helper who wears a cross. We went a little bit deeper and talked about specific rituals that were in that place. It wasn’t enough for the church to be such an influence in this area, they needed more, to go deeper. We chose to have the film occur in a place where the church already was by that time. Basing it in a time where the church was already in this area helped in the creative process.

What tools or techniques in Toon Boom Harmony proved particularly useful when making the film?

Patricio: We used Harmony for the cleanup, closer to the post-production stage. We did it for effects, lights, shadows and colour effects. Especially working with the line, we found that we could use brushes that we couldn’t find elsewhere. That gave this rough look to the final line that we wanted.

We wanted it to feel like a film made in the late 70s or early 80s, having a Xerox effect on the line. So keeping this raw aspect to the line was super important to us and I think that Harmony was really good for this. Iit was very useful for technical stuff like creating lights and shadows and masking them. We mostly used it in the final part of the film, for the final look of the characters, the line and the effects.

It was a mixture of analog processes, the backgrounds printed after being painted with watercolour then scanned. We wanted to give it an analog look to make it feel like an old film. We wanted to channel B-movie horror and the exploitation genre of film, which I’m a fan of. And we wanted to make it look like an 80s film somehow and I think the software was super useful for that — especially the brushes, as that look is very hard to create with fully digital animation.

Gervasio: Also it was really useful for the creation of the camera movements. With a few different sets we create a 3D base and then we draw over everything. But it was really useful to have the full background in the software and then be able to animate over the background. Then when we mix both things in composite or in the first pass of animation, everything makes sense. There was a communication between backgrounds and character that was constant.

The fact that we were able to import and export the file we created, a file we called mother file which was a .psd with the full export from Toom Boom Harmony with the background, the camera and the characters moving. That was really helpful to create some action and some motion in a way that made it easy to work between characters and backgrounds.

What is your advice for animation studios looking to qualify for the Oscars?

Patricio: We have been working with Miyu Distribution from France. We met them when we were still finishing the film, they were interested and have been distributing the film internationally. The film has been selected for around 50 festivals, and has won a few awards as well as being in the official selection for Annecy this year. It was great to show it to a European audience because, which is important, because this film is speaking on the relationship between Europe and Latin America.

It did really well in Latin America of course, we won in Guadalajara Festival in Mexico, and Chilhemonos Chile, which are both pre-qualifiers for the Academy Awards. Right now we are in the longlist of short films which are eligible for the best animated short-film category. It’s been interesting to have the film shown in many places, such as in Taiwan, and a premier at Chicago Festival in the US, as well as in New York and Canada now too. In Europe it’s shown in Denmark, in France and in Spain. The last few months have been interesting, with the festival circuit. We released it on October 12th, which is Resistance Day in Latin America.

Gervasio: We’ve been connected with institutions, embassies and the academy here in Mexico. It’s like everyone feels that the movie is touching and represents all of the countries. All of the countries that have been dealing with this cultural appropriation in Latin America. The same way that people were connecting, feeling like they’re contributing to a movie that is talking about something important, and also helping us with the campaign and getting the movie seen by as many people as possible. People are helping us and that’s really important for us, that the content and style and movie itself resonates – that’s already a win for us.

Any final words of advice for upcoming animators?

Patricio: Thanks to the film’s entire team, which as I said was huge and from many countries. We are both super thankful for them believing in this vision. In that sense, if I could give advice, it’s to trust your guts, even if your vision isn’t easy or suitable for the market. Art needs to be about things, not just entertainment. It should be both: entertaining while speaking about things that are important to you. Animation can be a very useful medium for that, and it hasn’t been fully developed in that sense yet.

I believe that animation from the Global South, and those of us who are Westernised but who are not Western, still need to develop our own languages and ideas and I think we can add something to the conversation in that sense. My advice is to take risks and trust in your vision, even when it’s not easy. Animation is like when you run a long run, you need to endure it. It’s important when you work in animation that you trust what you’re speaking about and doing something that truly connects with your inner ideas. That’s the way you make it to the very end, otherwise it gets tiring. Speak from your own truth and that will help you reach your final goal.

Gervasio: This conviction and belief in a story to be told, no matter what the language, the tools or the length. If you believe there’s a story to be told, whether it’s yours or somebody else’s and you contribute, all those projects related to the heart are the ones that are going to make you advance in life. Sometimes we have to work more commercially — to pay the rent — in that field the goal is different. It’s not always to tell the story, sometimes it’s to make money, and that can be frustrating.

But if you have these kinds of projects on the side, or you’re making work alongside friends, if you have the belief and the conviction, that is the beacon to advance. As Pat said, with animation you can do anything you want because there’s a blank page. You can write the story and create something meaningful, and that can inspire others to write their stories and tell important things that need to be told. That’s my suggestion for new animators and filmmakers: Trust your gut and participate in projects that speak to what’s important in life.

- Looking for more spellbinding work from the talented team at Ojo Raro? Be sure to visit the studio’s website.

- Interested in bringing your story to life? Artists can download a 21-day free trial of Harmony Premium.